An immediate volcanic threat threatens Iceland’s Reykjavik Peninsula, with scientists predicting that the Fagradalsfjall volcano is on the verge of erupting, possibly within the next few days or hours. However, there is even a possibility that a ventilation hole with a diameter of about 18 miles could soon appear.

Deep beneath the country’s southwest, magma is building up to a depth of 3 miles, forcing more than 3,000 residents of Grindavik to evacuate their homes, escaping a landscape reminiscent of apocalyptic scenes.

See a real-time image of the Reykjanes peninsula:

Under a state of emergency, the region is grappling with the unsettling reality of cracked ground, damaged roads and the looming possibility that Grindavik could be wiped out if the volcano erupts.

Iceland’s Meteorological Service, which monitors magma intrusion and movement rates, points to a “significant risk” of an eruption from a volcano that has been dormant for 800 years until 2021.

Professor Thorvaldur Thordarson, an expert on volcanology at the University of Iceland, supports an increased probability of an imminent eruption, estimating that it will unfold in hours or a few days.

The possible aftermath of an eruption raises alarming scenarios, with volcanologist Ármann Höskuldsson warning that the entire town of Grindavik could be at risk. The evacuated residents, recognizing the ominous prospects, have left everything behind, awaiting the destruction of the city.

A recorded 9 mile-long magma ‘river’ beneath Grindavik is fueling fears of a catastrophic eruption just below the town. Authorities allowed a brief return for residents to retrieve their belongings, underscoring the unpredictable nature of magma reaching the surface, posing a significant risk.

Icelandic MP Gisli Olafshonshared expressed growing concern on Platform X, highlighting the escalating seriousness in Grindavik.

Ground damage from earthquakes and magma-induced displacements increase the risk, while the possible sizes of magma chambers suggest a major eruption. The magma intrusion, which stretches 9 miles in length, raises fears of a fissure vent eruption, possibly surpassing the destructive effects of previous eruptions. Scientists warn of limited warning of magma spewing to the surface, complicating security measures in the area.

The preferred scenario calls for an undersea explosion to minimize damage, but concerns remain about possible disruption to air travel over Iceland, which is currently unaffected.

The precarious situation unfolds as residents prepare for the unexpected and scientists grapple with the volatile dynamics of the impending volcanic event.

Part of a global process in the lithosphere?

However, there is also a possibility that a huge ventilation hole could soon appear as the Reykjanes Peninsula runs right along a global fault, between huge plates. Therefore, the issue of the eruption does not just concern Iceland.

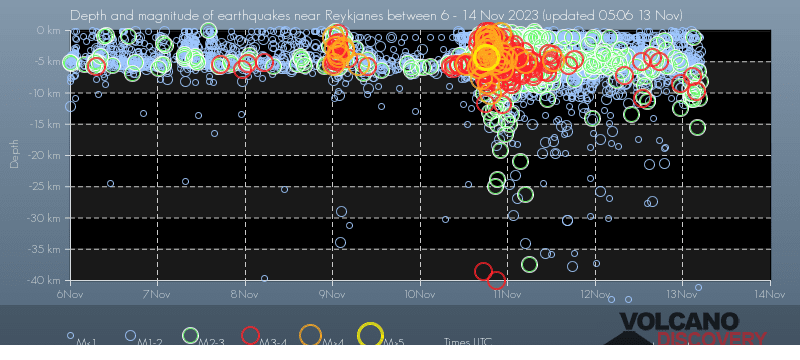

Now lets look at the depth map:

There is no such density of earthquakes as on November 11, but the trend of significant earthquakes at a depth of 6 miles will continue. And this is just the very bottom of the oceanic crust, then the mantle.

In addition, there are a lot of never before seen small earthworks at great depths which suggests that magma, having broken through some kind of barrier on November 11, is now rising and filling relatively small cavities. That is, there is some kind of constant influx of hot material that will sooner or later break out to the surface.

But the most important alarm bell is the correlation of the seismic situation in Iceland with gamma-ray bursts that occurred in September and at the end of August.

The standard reaction time of the lithosphere to such things is 2-3 weeks, after which nothing serious happened to the planet. However, there was nothing serious at visible depths, that is, where it works quickly. But if the reaction begins somewhere in the mantle, then it takes time for the magma to rise. And chronologically, this is exactly what happened – the first reports about the rise of the surface, about the increase in groundwater, came from Iceland in early October. But since Iceland is a country with frequent volcanic activity, no one paid much attention to the situation.

Meanwhile, a significant rise in the surface occurred on the Phlegrean Fields and on the Bonin Islands, where an underwater volcano had already started operating:

Etna began to work more actively, and earthquakes in the area of Mount St. Helens intensified.

These events allows us to think that the situation in Iceland is not some kind of local rise of magma that will break through and quietly flow out, but a global process that is now occurring throughout the entire lithosphere. And it will work according to the principle “it will break where its thinner.”

So far, Reykjanes seems to be the thinnest place, but the surface of the Earth is quite large, nearly two hundred million square miles, and geological science does not know where the first breakthrough will occur.