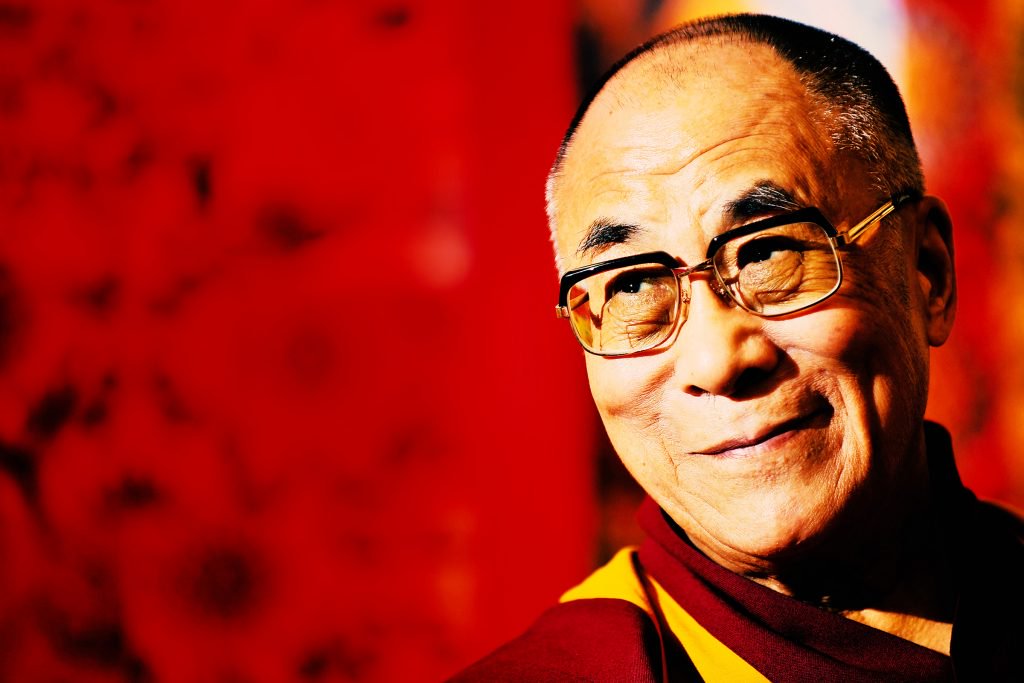

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader, has for decades travelled the world with a message of peace, compassion and love that has won him hundreds of followers and admirers, made him one of the most respected and recognised religious leaders around Earth and got him the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize.

“Love, kindness, compassion and tolerance are qualities common to all the great religions,” he wrote on his Facebook page. He has brought his message to Christian, Jewish and Muslim leaders, such as Catholic Popes john Paul II and Benedict XVI, and lately spoke on behalf of the Rohingya muslims since they suffer ferocious persecution in their predominantly Buddhist Myanmar home, sometimes at the hands of Buddhist monks.

However, the Dalai Lama’s tolerance doesn’t seem to expand to devotees of Dorje Shugden, a contentious Buddhist deity to whom the Dalai Lama himself has admitted that he used to offer prayers before announcing it to be a malign spirit. Such appears to be his aversion to Shugden practitioners he has asked them to not attend religious parties where he is present.

He has since 1976 affirmed on several different occasions that the practice of paying devotion to Dorje Shugden shortens the life of the Dalai Lama, promotes sectarianism among Buddhists and signifies a “danger to the cause of Tibet”. Through such remarks, Tibet’s de facto religious leader efficiently issued a prohibition against the practice, resulting in ostracism of its practitioners by the wider Tibetan Buddhist community.

Some Shugden practitioners say that this is comparable to the Pope threatening excommunication for people who promote devotion to the Virgin Mary or Saint Francis. Such high-handed actions would meet with fierce opposition both from people and from orders like the Franciscans and the Marists. All would no doubt consider themselves practising Catholics despite their obvious disobedience to a figure that, in Catholic doctrine, is God’s representative on earth.

An issue of emphasis

The Dorje Shugden deity is believed by some to be among many protectors of the “Geluk”, or”yellow hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism to which the Dalai Lamas belong and whose adherents are known as “Gelukpas”. Critics state worship of this deity promotes divisions among the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, all which share the same fundamental doctrine, and whose differences lie mostly in the emphasis they put on various Buddhist scriptures.

“The hub of the dispute is contrasting views on sectarianism and the correct path for Yellow Hat Buddhism,” wrote M.A. Aldrich in a December 2016 article at The Diplomat. “The Shugden followers insist upon an aggressive purge of heterodox forms of Tibetan Buddhism while the Dalai Lama has called for non-sectarian cooperation among all branches of Tibet’s religions.”

Shugden practitioners have worshipped among “Yellow Hat” Buddhists for some 350 years. If they’ve pursued an”aggressive purge” of different kinds of Buddhism, as their accusers state, how can it be that all four main schools of Buddhism generally flourished over such an extended period?

Moreover, since Shugden devotion has been an accepted practice for most of this period of time, what has changed since the Dalai Lama fled Tibet in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese Rule?

“The Dalai Lama believes that aggressive sectarianism threatens Tibetan unity,” wrote Aldrich. “He has decreed that while the followers of Dorje Shugden may continue to worship the deity, his own followers should not permit devotees of Shugden to be initiated into the Kalachakra.” The Kalachakra is a intricate system of doctrine and meditation in Tantric Buddhism and exclusion from it is seen by many as a significant penalty.

Though the Dalai Lama has said his statements don’t amount to a ban on the practice, the Central Tibetan Authority — the Tibetan government in exile in India — taking its lead from the religious leader — has made a range of moves to ostracise Shugden practitioners. A 1996 CTA resolution involves a clause which states: “if individual citizens propitiate Shugden, it will harm the common interest of Tibet, the life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and strengthen the spirits that are against the religion.”

Other branches of the exiled government immediately fell into line after this resolution. For instance, a 1996 directive from the CTA’s department of health said “if there is anyone who worships Dorje Shugden, they should repent the past and stop worshipping. They must submit a declaration that they will not worship in the future.”

Demonizing worshippers

Jamyang Norbu, a Tibetan political activist who favours the independence of the area rather than greater autonomy under the Chinese authorities, states that although the Dalai Lama has every right to object to Shugden practices on theological grounds, Buddhists ought to be free in their devotional practices.

“The trouble is that the Tibetan government has been inducted to implement the Dalai Lama’s proscription of Shugden worship,” wrote Norbu. “The Tibetan government claims it has not issued any orders or appeals to people to harass or fight Shugden worshippers. Yet it has produced and distributed literature and videos demonizing Shugden worshippers.”

Norbu is nevertheless highly critical of those outspoken Shugden activists who’ve picketed a number of the Dalai Lama’s public appearances, trying to drown out his words, chanting abuse while making no attempt to engage into dialogue. He has stated, however, that additional effort can be made to achieve an understanding with those Shugden acolytes who continue to accept the Dalai Lama as their spiritual leader.

One such is Tsem Tulku Rinpoche, the Malaysian based ‘spiritual advisor to Kechara’ Buddhist Temple and Shugden practitioner, who earlier this year said that he was”ecstatic” about what he known to be a perceived softening of the Dalai Lama’s position vis-à-vis Shugden practitioners.

A number of Shugden centers, such as Kechara, state they’re not in any way active in the autonomy debate, nor have no curiosity about overtures from China.

Tsem Tulku Rinpoche says he has for decades resisted the scapegoating of the Shugden spiritual practice, looking for a peaceful end to a conflict that has already weakened the beleaguered community of Tibetan refugees and their Tibetan government in exile. Additionally, supporters say the exception of Shugden practitioners isn’t compliant with the Tibetan constitution, nor Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that embodies the notion of religious liberty.

Another notable Shugden exponent to come under pressure would be Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, religious leader of the New Kadampa Tradition. Supporters maintain these two leaders have worked tirelessly spread of the Geluk tradition globally. However, while the New Kadampa tradition has protested the Dalai Lama vociferously, Tsem Tulku’s Kechara followers have sought to avoid this conflict.

Nevertheless, the vilification of the practice persists. In late 2016an official correspondence from the Tashi Dargyeling Monastery — as translated on a Shugden-leaning website — seemed to promote measures against Shugden professionals which bear all the hallmarks of religious persecution. People who continue to worship the deity, or just maintain relationships with practitioners, are told that the monks of the monastery won’t perform prayers in their homes or funeral rights for members of the family — somewhat equal to being excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

Earlier in 2016, a Monastic University in the Tibetan exile community stated that it had introduced an identity badge program for its monks to indicate they weren’t “Dolgyal propitiating monks”. Dolgyal is a derogatory term used for Shugden devotees. Monks who practiced dedication to the Dorje Shugden weren’t welcome in the school, it was understood.

More alarming still, there also have been widespread reports of beatings, vandalism and death threats targeted at practitioners, a lot of whom say they’ve been forced into the boundaries of their communities, or to leave them completely.

A Chinese angle

“There’s a lot of passion around this (issue) from Shugden practitioners, and the Chinese have fostered this Shugden worship as a way to split Tibetans,” explained Kelley Currie, a senior State Department adviser on Asia and Tibet from 2007 to 2009, told Reuters in a December 2015 report. Currie has worked for the International Campaign for Tibet, an advocacy group promoting human rights for Tibetans.

In the last several years, Dorje Shugden professionals have been denounced as stooges of China who support Beijing rule in Tibet. They’re accused of allowing China to exploit divisions among Tibetan Buddhists and worse, accepting Chinese backing to foment discord among the exiled Tibetan community.

Their virulent opponents have established a string of attacks through social media, including a high number of heavily-worded insults and threats on Twitter, Facebook and elsewhere, couched in an occasionally violent speech rarely associated with Buddhism. Shugden proponents who share their spiritual practices online say they risk a co-ordinated deluge of frequently ad hominem attacks.

The timeline of events additionally indicates it had been the edicts and pronouncements from the Shugden practice which generated the discord within the Buddhist ranks in the first place. If Shugden acolytes were permitted to keep their worship practices unmolested by other factions within the Buddhist community, as they’ve done publicly for 350 years, there could possibly be no schism to exploit.

In effect it seems that it was just after the Dalai Lama spoke against the practice that the Chinese authorities made its first tentative approaches to Shugden practitioners, possibly sensing a chance to exploit the rift and weaken the push for Tibetan autonomy.

Nevertheless, China is not involved in the demonstrations, said Sonam Rinchen, a U.S. based Tibetan national, as mentioned in the Reuters piece. “I am sure they are pleased, but we do not protest to please China,” he explained. “We are interested in getting our religious freedom back.”